When I first started web scraping, I didn’t really know much about how AJAX or the DOM worked. I thought everything I needed to know was the HTTP protocol and I’d be good to crawl any page I wanted. Unfortunately, I was wrong.

In this post, I’ll show you a workflow for crawling edX’s website and get pertinent course information such as name, university, instructors, ratings, etc. I’ll be using Python’s Scrapy framework and google Chrome’s dev tools (they come natively, no need to install anything).

Note that I’m writing this post on October,2016. If you’re reading this in the future, the layout of this site might have changed and the crawling might not work anymore.

Before we begin, I’d like to say 2 things: the first one, which is the most important to crawling (and to all informatics, by the way), is to try to keep it simple (I’ll give some examples later on), and the second one is how AJAX works. So, let’s start with the second one.

When you access any webpage using your browser, you usually type something like http://google.com (notice http:// in the beginning!). The browser you’re in (even if you use Internet Explorer) understands this as “Make an HTTP request for google.com”. This request is gonna contain some data (the type of request (GET in this case), your IP address and other stuff). Google is gonna accept that request and send an HTTP response to your browser. Inside that response’s body there will be contained the html of google’s front page we know and kinda love.

Then you will write something in the search bar and hit enter. This will perform another HTTP request with different parameters (one of the parameters will contain the terms you searched), and the response is gonna contain the page with the results for the terms you searched. And it goes on and on.

AJAX stands for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML, and it’s basically a way of cheating the HTTP protocol. Using edX’s website for example: when you search for courses in the page, it loads the first 9 results (loading 100 results in one page would be aesthetically unpleasing). When you scroll down to see more results, the normal HTTP protocol action would be to render a new webpage with 9 + 9 results and send it to you. But that way, you’d be transfering a lot of data you already have (the layout of the page and the first 9 results). Imagine scrolling down 100 times and the ammount of repeated downloads we’d produce.

So that’s when JavaScript can come in for edX’s website, for example (it can be used in many other cases). Explaining in a high level, edX’s developpers tie the “scroll down” action with a JavaScript function that’s gonna send an HTTP request to edX’s server asking for the next 9 courses. The server is gonna answer with an HTTP response containing the 9 courses in it’s body. Another function is gonna append the new 9 courses to the already rendered page instead of reloading the new page. In other words, the new 9 courses are gonna be appended to the DOM, which is the structure that the browser interprets for us to see. You can think of it as the interpretation of an HTML file.

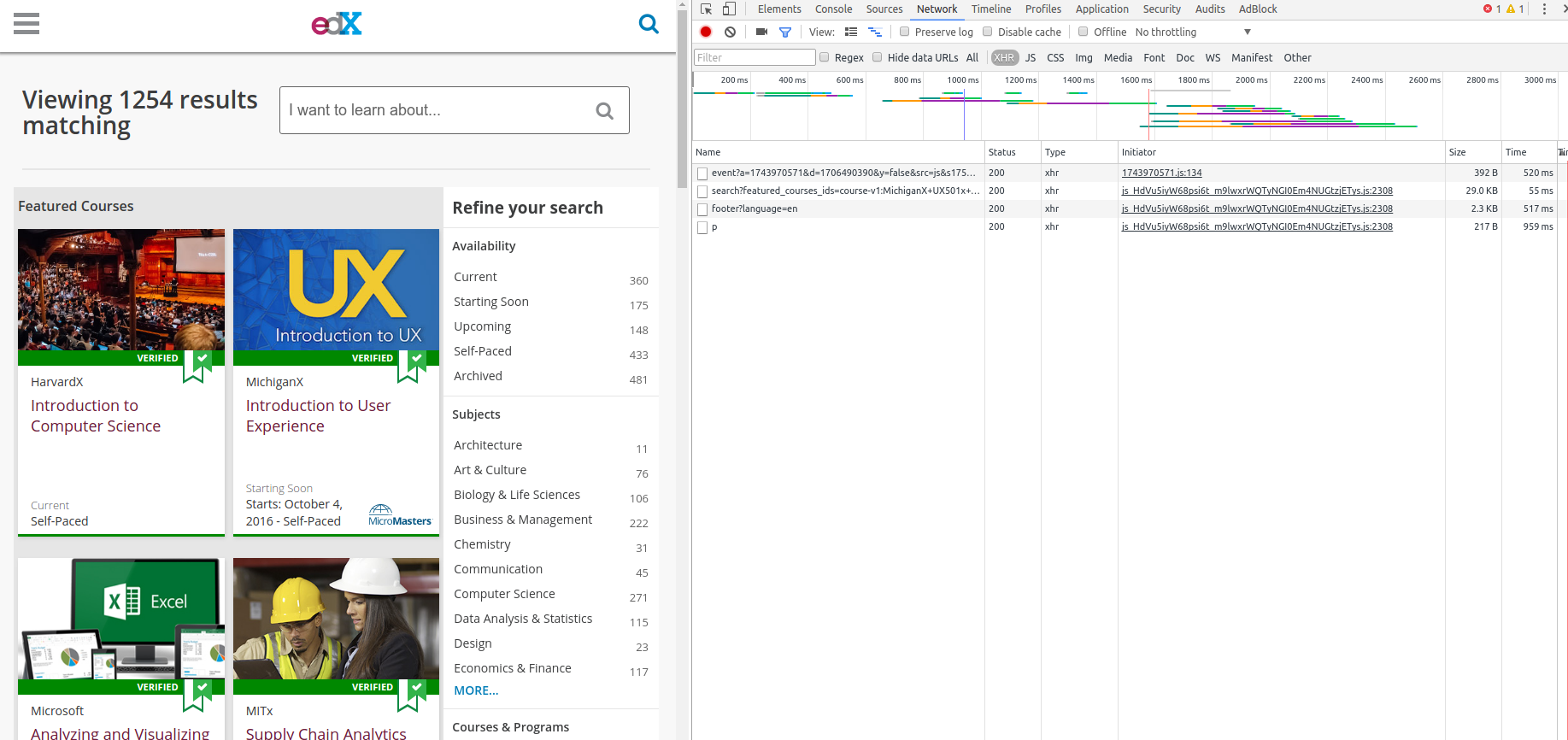

There’s a lot more to HTTP and AJAX, but hopefully that will be enough to get us started. It’s called web scraping for a reason. The first thing we’ll do will be opening Chrome and pressing Ctrl+Shift+i to open the “inspect” tab. After that, click the tab network. Let’s go to https://www.edx.org/course. Your browser should look like mine right now:

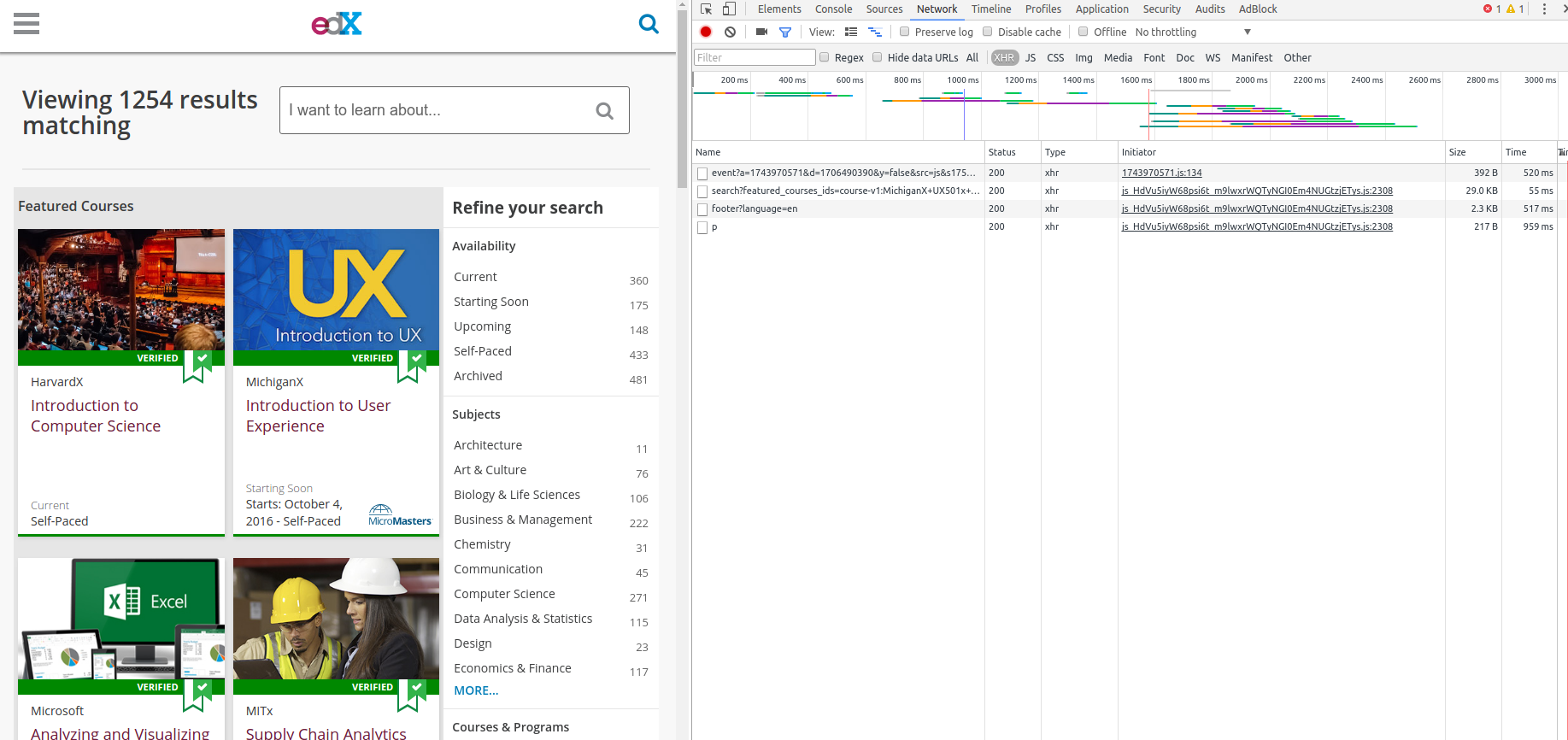

Now scroll down the page to see more courses (be prepared: as I told you earlier, it’s gonna trigger a JS function to get more elements! Expect network activity). The network tab should look like this now:

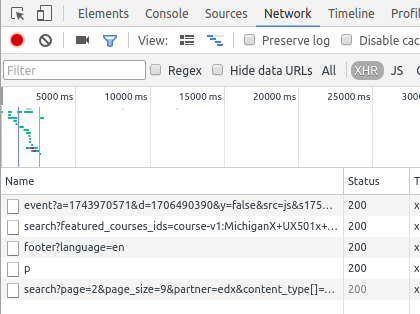

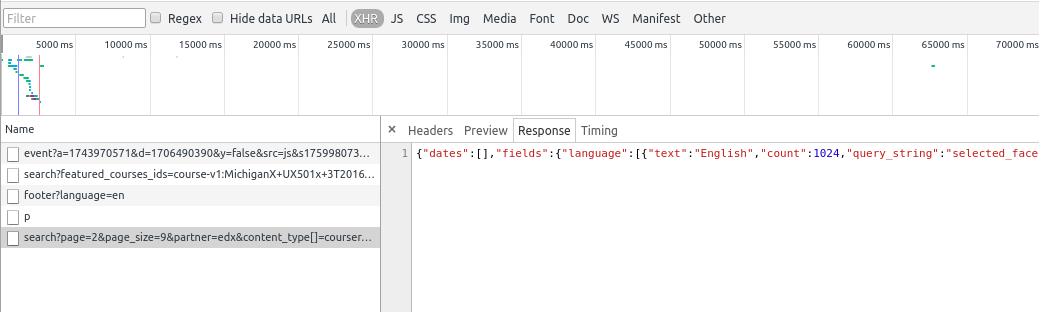

Aaaaand we hit the jackpot: click the last response received (search?page=2&page_size=9&partner=edx&content…). After that, click in the response tab to see the contents of it. It should look like this:

See the thing between “{}”? That’s called a json, and it’s basically the format AJAX data is transfered. If you copy all that and paste in a notepad, you’ll see it contains many useful information about the courses, such as it’s name, the institution that provides it and of course, the link to the course’s page. It’s a good time to start using scrapy. Go to the terminal, start a project with scrapy startproject edx. Change to the folder edx and create the script spiders/edx.py, and write the boilerplate for a new spider:

So, we’ve seen that sending an HTTP request to “search?page=2&page_size=9&partner=edx&content” sends us back a json containing a lot of interesting data. So the first step is to convert that json to something python can handle. data = json.loads(response.body) does that for us. If you execute this bit of code with scrapy crawl edx --nolog, you’ll see:

So, the data received is a dictionary with a bunch of useless stuff to us. The important information about each of course is located in data[u'objects'][u'results'].

So, with this request we can get the title, description, organization and lots of other fields of each course. But this only gets us 9 entries at a time. What if we changed page=2&page_size=9 in the SEARCH_URL to page=1&page\_size=1254 (1254 is the number of courses in edX), would it work??? In this case, it did. If we want to save the information we got, all we need to do is create an item to store all that and put the fields in it. If we’d like only the ID’s from each course, we could write an item like this:

Let’s now modify the spider’s code to actually produce the items. It’s pretty straightforward:

If you’d like to save the results to a csv, all you’d need to do is execute scrapy crawl edx -o out.csv -t csv.

You can see a more complete version of the crawler in this repository. It gets additional fields such as review data, instructor names, etc. For that, it uses the same priciples detailed here. Ah, I almost forgot! The part about keeping it simple: We were very lucky edX’s website had an API system to get course data, that the API didn’t need any kind of token or authentication and that it accepted for 1000s of items to be fetched at once. This allowed the code to be very simple and easy. It’s not always like that; but it sure is good when it happens. So, before scrolling page by page, using a webkit or other sophisticated solutions, stop and think if there isn’t an easier way of doing it, because there usually is.